Lidar unboxing day: A few southwest Virginia treats within ~1 hour of Blacksburg and Virginia Tech

by Philip S. Prince

I always look forward to my first look at high-resolution lidar imagery from a familiar area. Last week, I took time to check out some some new-to-me imagery from areas surrounding Blacksburg, Virginia, where I spent about 10 years studying and then teaching at Virginia Tech. I found the following features particularly interesting, as I have regularly viewed or even walked across all of them without appreciating their presence!

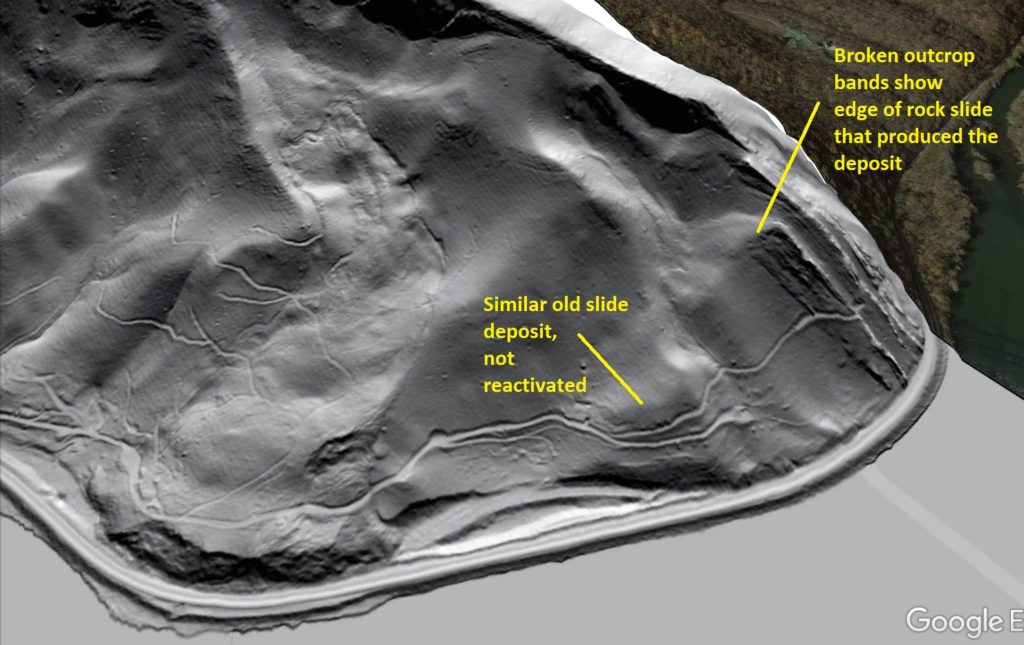

- Huge, historically (<100 years) or currently active debris slide, New River above McCoy Falls, Pulaski County

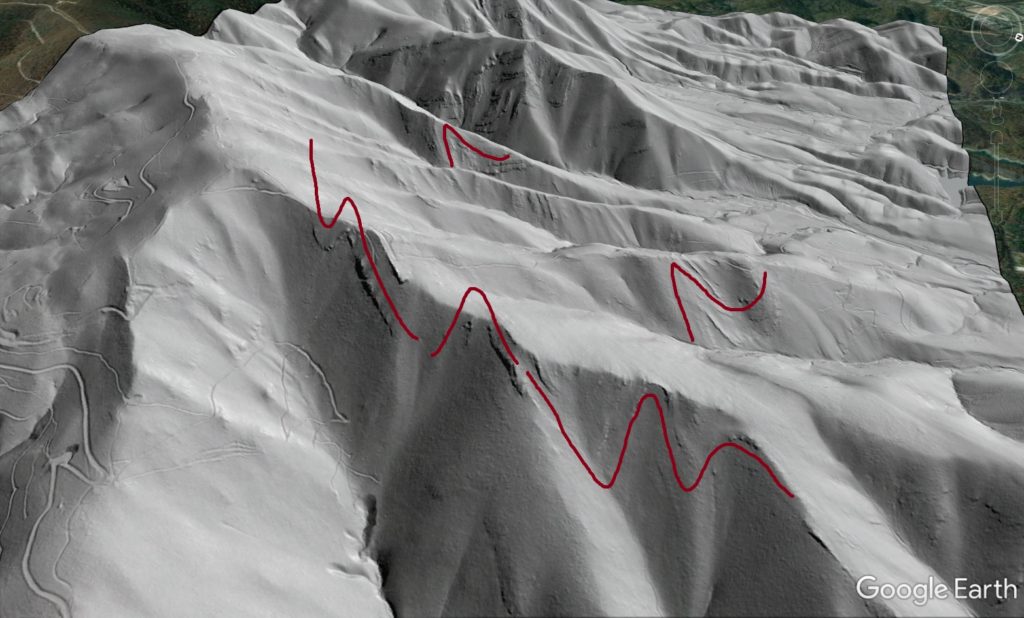

This slide, which resembles a glacier creeping down towards the river, has developed in the debris pile produced by a large rockslide on Walker Mountain. The rockslide laid bare white cliffs of Tuscarora Sandstone that I have always heard called “White Face.” The rockslide is ancient (Pleistocene?), but activity in the resulting debris pile is much younger. The GIF below shows the slide and its topographic context. White Face is visible at the very top center in the aerial photo image. The curving path of the slide can be appreciated from this perspective. I have looked across the river at this area hundreds of times, so this 1-meter hillshade view is very satisfying!

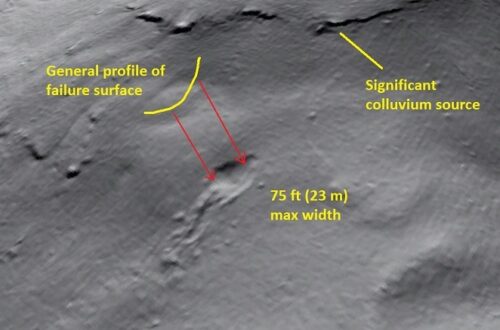

To me, the most striking feature of the slide is the crispness of its lateral scarps and headscarp. They don’t appear to be very large, but remain very crisp and well defined, suggesting recent or ongoing activity.

The edge of the slide can be seen cracking along the left-lateral scarp as material pushes up and out of the topographic low that holds the debris deposit.

I can’t personally speak to the movement history of the slide, but I suspect that removal of a portion of its toe to construct the railroad running along the river may have led to reactivation. A smaller slide to the north (right side of the image) was not altered by railroad construction, and looks very old and stable compared to its large neighbor.

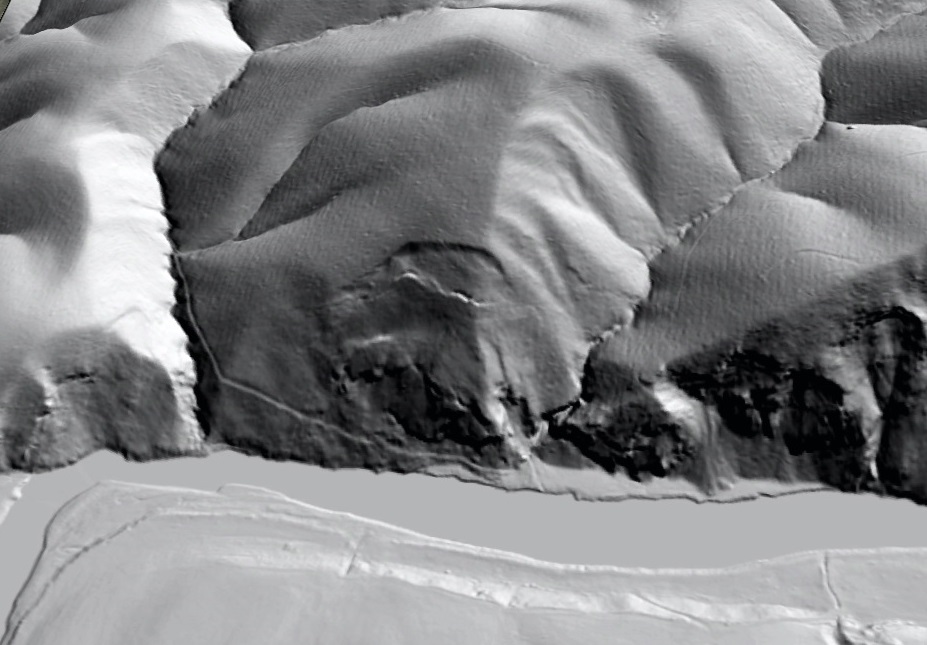

2. Rock blockslide along Big Reed Island Creek, Pulaski County

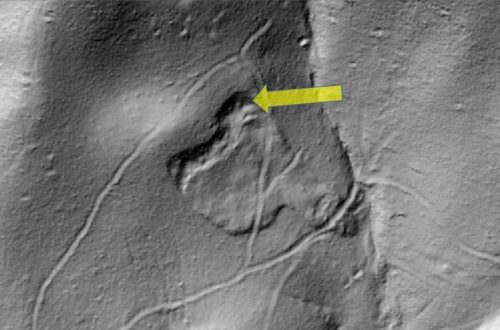

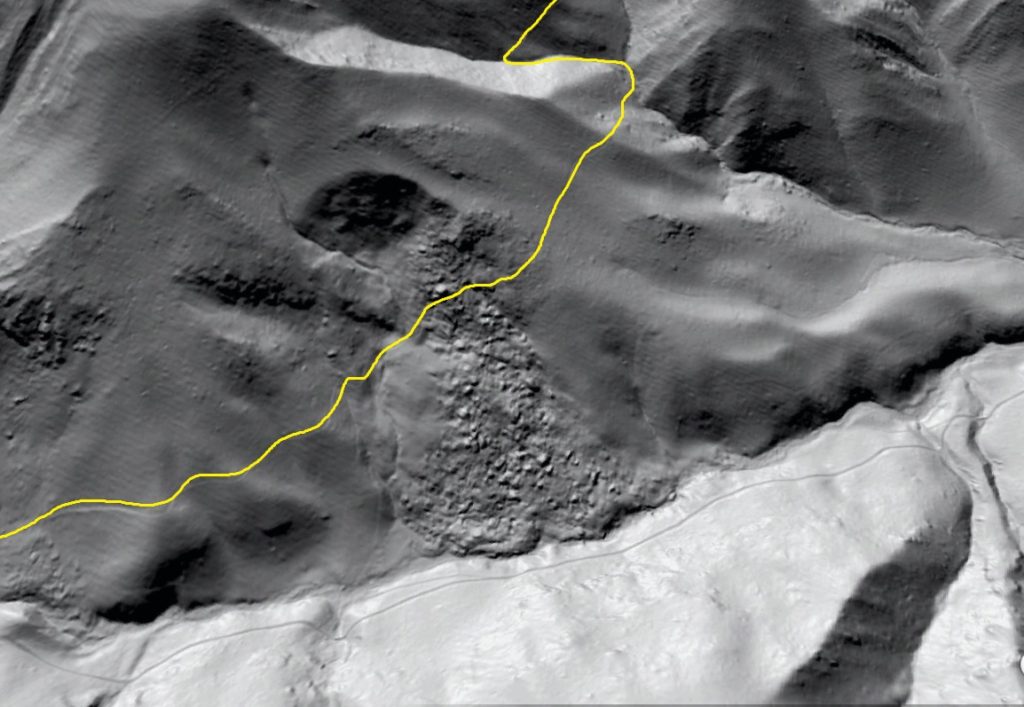

This slide has experienced little displacement, but lidar reveals an impressive graben that is forming as a large mass of Hampton Shale (really a slate or phyllite here) bulges outward from the riverbank as it is undercut by Big Reed Island Creek. The slide and graben are at the center of the image below.

The graben and slide are, unsurprisingly, invisible without a lidar-based image.

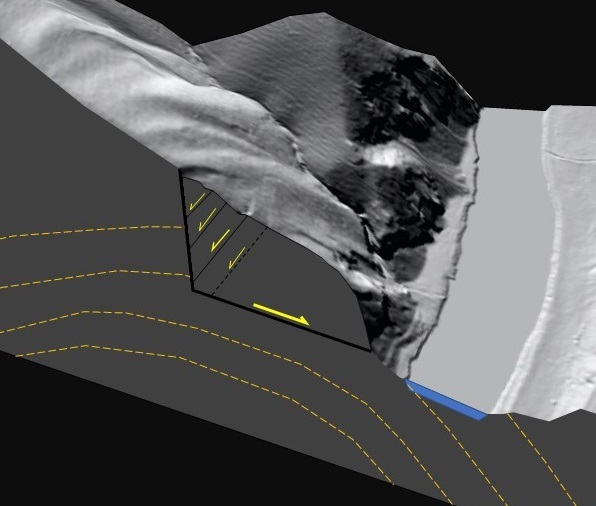

The graben is quite large compared to the overall scale of the slide. I think this indicates that the basal sliding surface slopes less steeply than the land surface, meaning the slide mass is thick and deep, particularly at its upslope end. The block diagram below attempts to illustrate this idea.

This slide is included on the Hiwassee quadrangle geologic map (linked here), and structural data indicate the failure is occurring along the crest of an anticline that plunges northeast. The basal sliding surface could therefore be a bedding plane/foliation plane failure whose low dip is an expression of where it sits within the fold structure,. The orange form lines in the diagram generally indicate layering orientation as it might appear on this cross section cut, which is at an angle to the fold axis.

I actually went to the foot of this slide with Virginia DGMR geologist Matt Heller during a canoe transect of the map area in June 2019. The poor photo below shows what the downslope end of the slide looks like, right above Big Reed Island Creek. This huge outcrop sheds plenty of rock, and does not feel like a place you would want to stand around for too long.

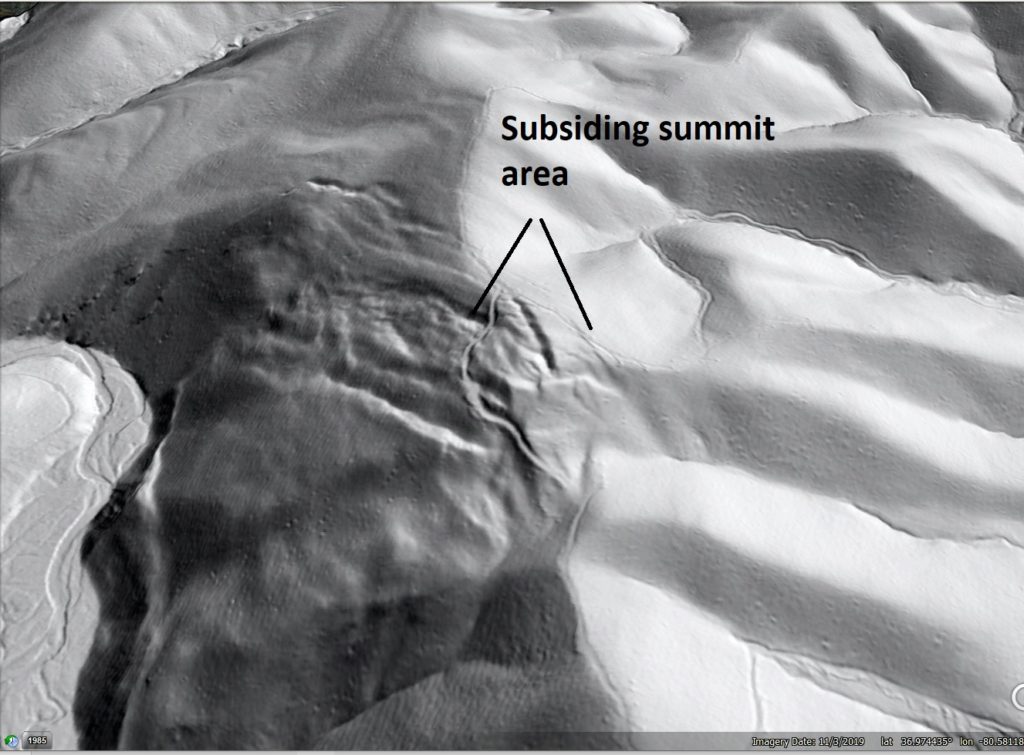

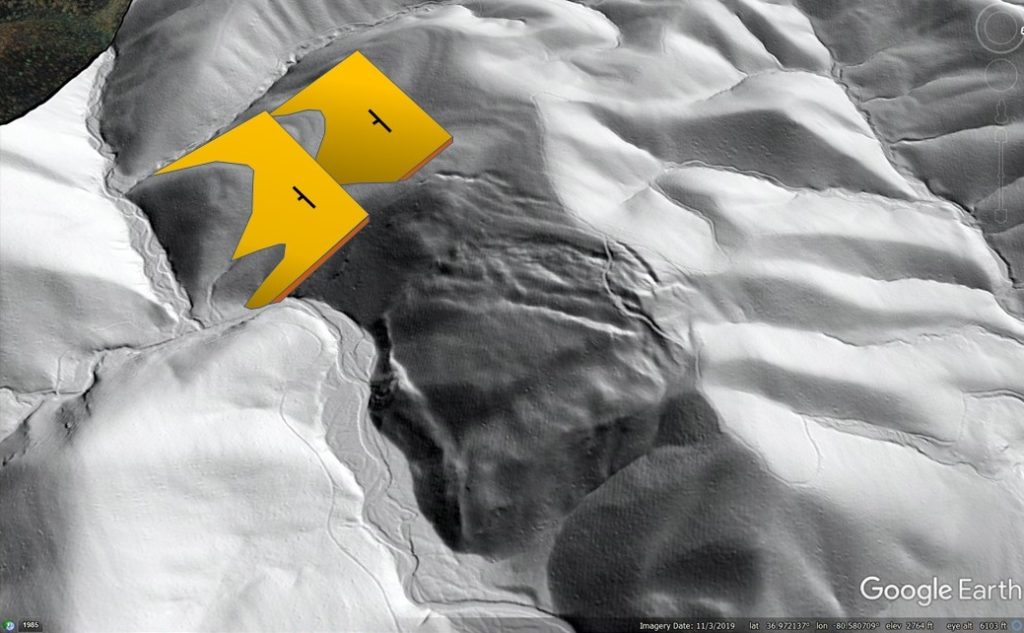

3. Buck Hollow Ridge rock slope deformation, Macks Mountain, Pulaski County

This slope movement is not far from the Big Reed Island Creek feature, and occurs in Erwin Formation quartzite just up-section from the Hampton Shale. Sub-surface failure within the Hampton Shale may have actually caused the movement, but I don’t know for sure.

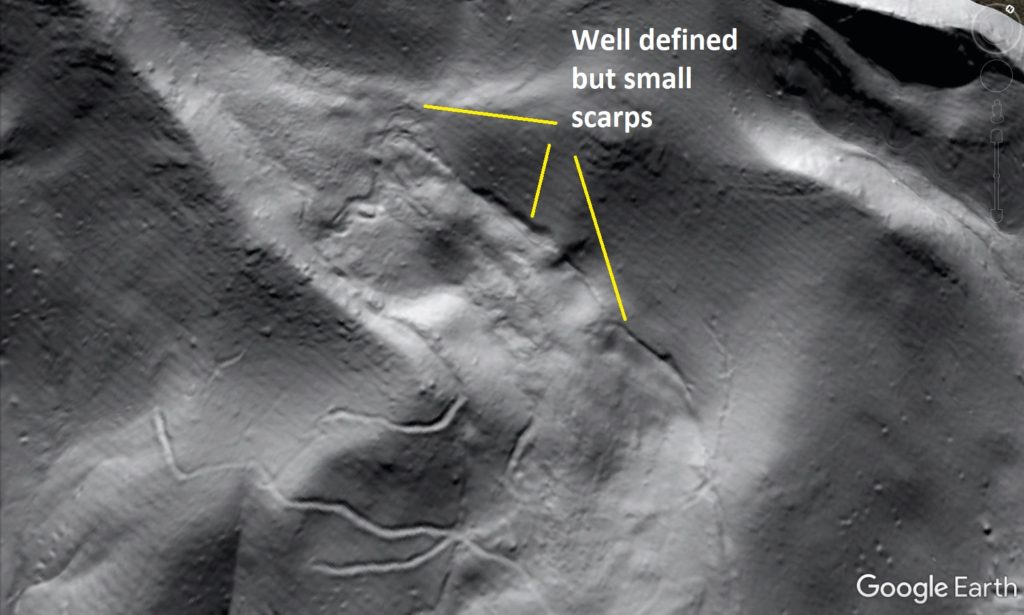

This failure indicates the precarious stability of some rock slopes (particularly dip slopes) in this part of Virginia, even if they host resistant rock types like quartzite. I have hiked along the toe of this feature before, and never knew it was there. The logging road grade along the summit cuts right through numerous scarps. I think this feature is particularly interesting because the headscarps are found on the back side of the ridge crest, meaning the summit of Buck Hollow Ridge has lowered slightly due to the failure.

The slide has developed on a dip slope, with slate/phyllite beds being the likely seat of the basal failure. Dipping quartzite beds nearer the surface are visible in the lidar imagery, as are subtle flatirons within the landscape around the slide. Progressive undercutting of the toe by Big Laurel Creek may have kept this sliding intermittently active for a lengthy period. It makes me wonder what a large-scale, man-made cut along the toe might do…

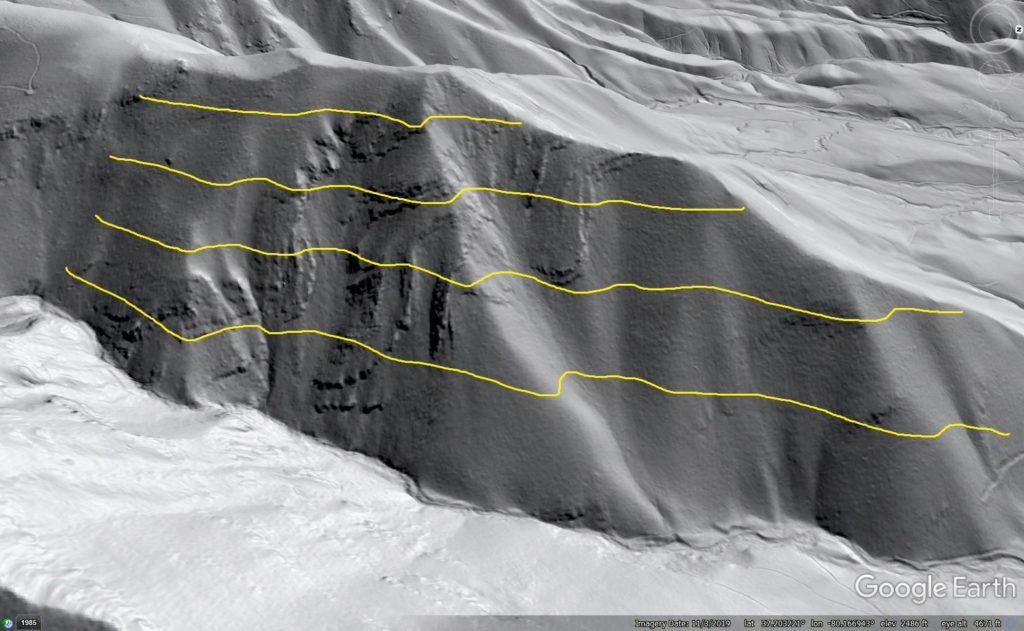

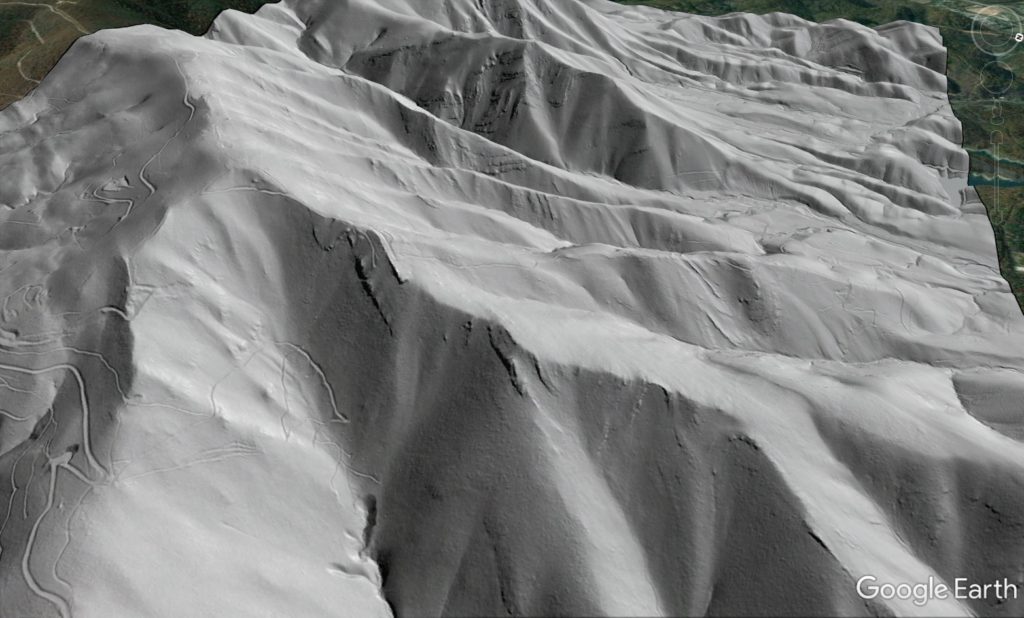

4. Folded Chilhowee quartzite beds on Poor Mountain, Roanoke County

Poor Mountain is topographically impressive. It absolutely looms above Interstate 81 south of Salem. Despite its size and steepness, its slopes are mostly forested and minimal outcrop is visible. Lidar hillshade imagery shows nice folds in the basal Cambrian/latest PreCambrian Chilhowee quartzite that supports Poor Mountain’s steepness and elevation.

The obvious folds extend about 2,000 ft (600 m) over the land surface in the image above. Their amplitude is exaggerated because they are viewed on a slope and not in a vertical cut, but folding is definitely present. The yellow lines in the image below approximate contours on the land surface, and beds can be seen to cut steeply across contour before paralleling it, and then cutting across it again.

Folding is extensive in the Chilhowee is extensive across the northwest face of the mountain. The lower image below uses lines to call out some of the structures in the foreground.

5. Rock Castle Gorge rockslide, Patrick County

Rock Castle Gorge is actually named for clusters of terminated quartz crystals found in the area, but its Blue Ridge Escarpment location makes it a very rough and rocky place at the larger scale. A main loop hiking trail through the gorge passes through the upper portion of the rockslide shown below, which is conspicuously bouldery and rocky to an observer on the ground.

The still image below shows what I believe to be the route of the hiking trail. I have walked the trail several times, though not for a number of years.

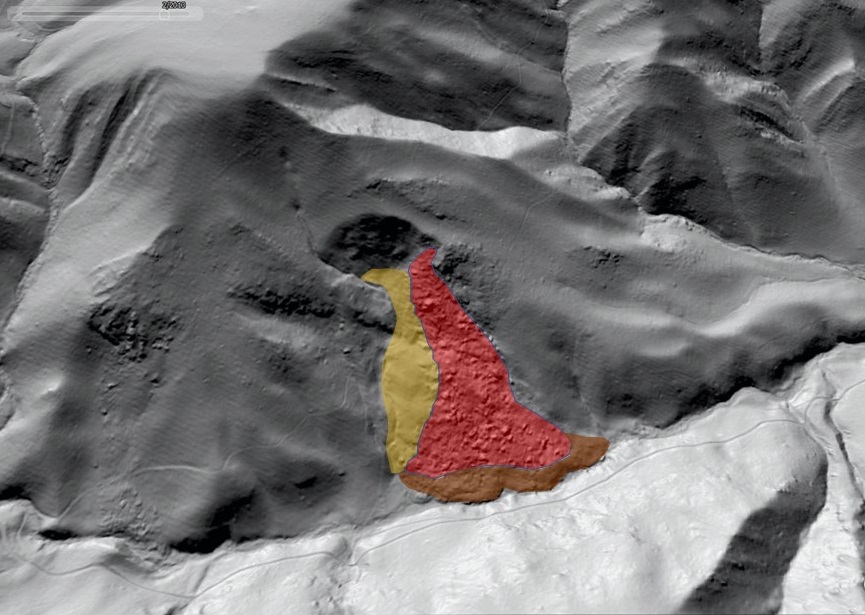

The texture of the slide mass shows the presence of different materials, which are likely schists and amphibolites. The chunky, bouldery material appears to overlie less bouldery material, and is also partly buried by less bouldery material derived from upslope. The bouldery material is clearly derived from the resistant horizon cut by the slide. I have tried to delineate these material-specific zones below.

A visit to this feature would quickly indicate how the stacking order of material in the slide mass reflects position of the in-place materials on the slope. Whether this slide is the result of a single failure or successive failures is unclear. It is also somewhat unique in the area. Despite its steepness and the frequent occurrence of dip slopes, the Blue Ridge Escarpment and its intensely folded metamorphic outcrops seem to host far fewer landslides than the folded/faulted sedimentary Valley and Ridge to the west.